The following is an excerpt from an op-ed that appeared on Truthout.org

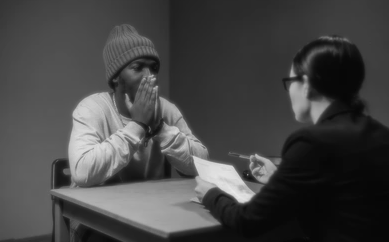

The first thing you’re aware of when you talk to someone in prison on the phone is that this is more than a two-way conversation. About every three minutes, a cold, robotic voice interrupts the flow of ideas with the standard “This call may be monitored or recorded” disclosure. Those seven words send a message far beyond the obvious: Not only are prisoners under constant surveillance but their environment is designed to be disruptive and disorienting. This applies to telephone communications as well as text messaging, which California has made available via providing prison-issued tablets. To add to the disorientation, the tablets are janky, spasmodic and constantly breaking down.

Over the three years we’ve known each other, [Ivan] Kilgore and I have learned to tune out the recording and we’ve developed a language that allows more delicate topics to be discussed at a surface level but understood on a deeper level. This is not an uncommon phenomenon: Have you ever been at a bar with a close friend, laughing wildly at something the other person said and no one else gets it? Language develops its own rhythm in each relationship, be it a friendship, partnership, or a journalist and a source. What sets prison communication apart is how long and tedious a process it takes to develop that language.

This is likely due to the absence of certain things we take for granted as people who are not living in that environment. In prison, there is no right to privacy, no freedom of speech or consistent contact. While some of these things may exist de facto, everything in prison comes at a cost.

Another incarcerated activist I profile in my book, Reimagining the Revolution, was sent to the security housing unit — known colloquially as the SHU or “the hole” — after our final interview. We communicated indirectly after that through mutual acquaintances. Earlier this year, Kilgore won a summary judgment against correctional officers at Salinas Valley State Prison — the facility that imprisoned him before his last transfer — and he has now begun losing telephone privileges and receiving a higher than normal amount of harassment from the guards at California State Prison Solano, where he is currently incarcerated. These consequences aren’t explicitly associated with being outspoken, but the connection is never subtle.

Some readers will detect a hierarchy in the latter anecdotes and, yes, there is technically a scale for in-custody offenses. Someone involved in a violent act may end up in solitary confinement, while someone who doesn’t make their bed may simply temporarily lose yard time. However, there is a long-term consequence to any infraction that evens out that scale. Infractions or disciplinary “shots” are consistently used as reason to keep someone in prison. Kilgore, for example, became eligible for resentencing under new criminal justice reform legislation, but his disciplinary record, which includes minor infractions, has caused his petition to be denied over and over again. Even though he has dedicated his time in prison to giving back to the society that locked him up — fundraising for a youth basketball team, creating a nonprofit that seeks to advance poor, rural communities and offering college students challenging yet rewarding internship experiences, just to name a few examples — he continues to be defined as someone lacking rehabilitation.

Through much trial and error, Kilgore has identified some concrete adjustments outside organizers and journalists can take to safeguard lines of communication. He encourages the people he works with to secure a “confidential mail” or “legal mail” status, which protects some communications under privilege laws (at least in theory). This can be accomplished by collaborating with a prisoner rights attorney, for example. In-person visits can also make conversations more intimate. While recording devices are not allowed in many prisons, you can take notes. Incarcerated people may also want to take steps to protect their identities when publishing their own writing. When I edited the All of Us or None newspaper, I had incarcerated writers who opted to use pseudonyms.

I would add one additional suggestion: Know before you go. Journalists are trained to be a “jack of all trades,” to know a little bit about everything so you can jump in and cover anything. Hopefully by now you’ve realized that a surface understanding of prison will not suffice. If you intend to embark on one of these painstaking but essential conversations, know your rights; know their rights; know how the prison department in that particular state is supposed to function and how it actually functions (most prisons function with very little oversight). Learn as much as you can about the person you’re talking to before you actually talk to them. See if they’ve written articles, or books, or have been interviewed before. Put all the cards on the table: Define what you are working on, how your interaction may impact them and what options they have to safeguard themselves.

The stories of inhumane prison conditions and injustices inflicted upon the people locked up in the most incarcerated nation in history need to be told, but not at the cost of journalistic integrity, and certainly not at the cost of the people willing to tell those stories.