Failed Progressive Measures in California Reflect Leadership Shortcomings, Not Identity

Last week, the Los Angeles Times suggested the failed progressive measures on the California ballot may indicate a transformation in the state’s political landscape. Having examined the progressive movement in California as a journalist, I likely would have come to the same conclusion if it had not been for the two years I spent embedded in it. From that perspective, it’s hard to see the election results as an identity crisis.

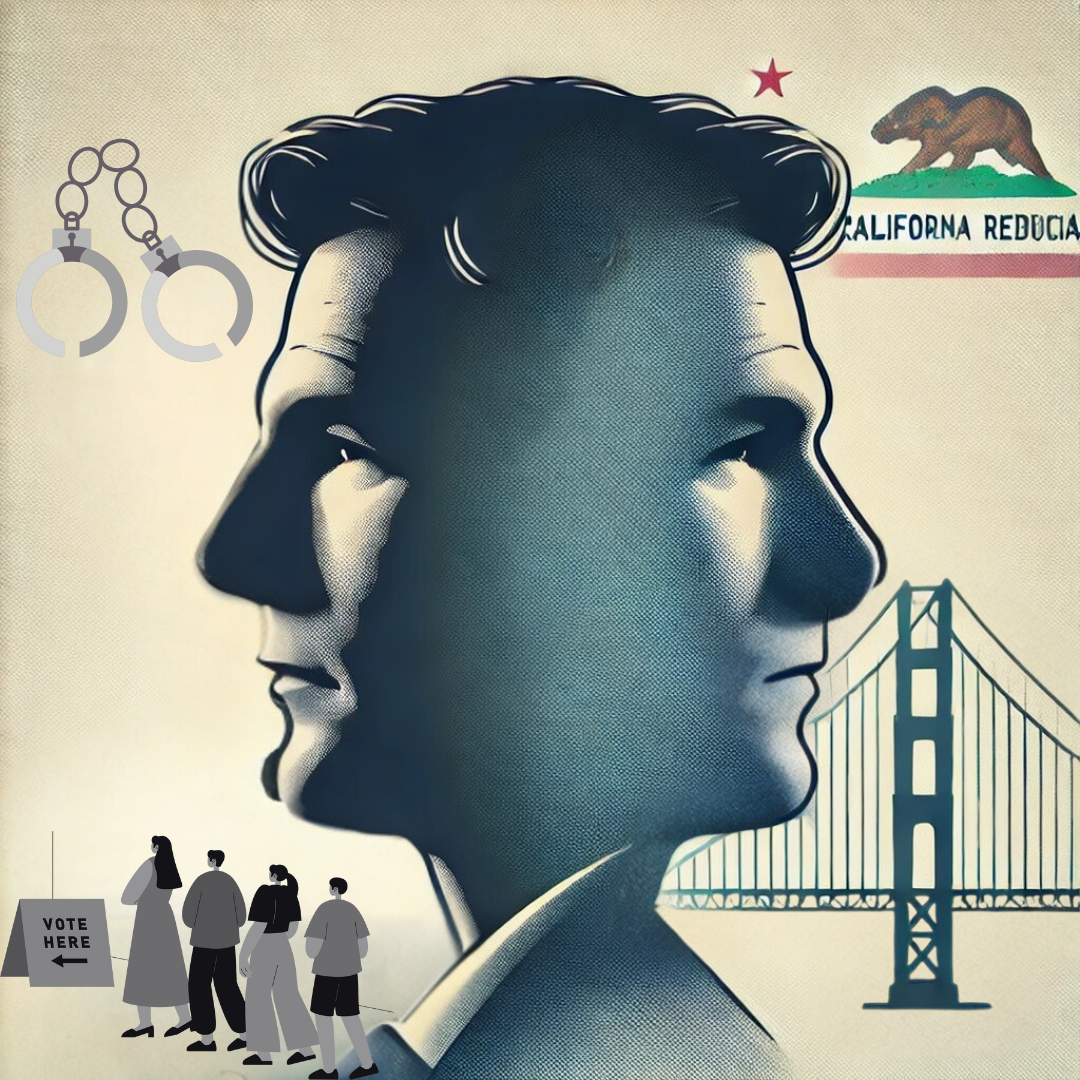

Perhaps the most telling experience I had was during my brief tenure with Chesa Boudin in 2020. Boudin, a former public defender, had just been elected San Francisco District Attorney and faced an intimidating environment to say the least—lawyers often cling to structure and hierarchy, and many of them seemed unsettled by the notion of a former adversary standing at the helm of the office. As his communications manager, I watched Boudin struggle to win over the office and still deliver on his campaign promises.

One of his first initiatives was to end cash bail in the city. I drafted a press release that echoed his campaign messaging, but the chief of staff at the time urged for a nod to his predecessor Geoge Gasćon’s work on the issue: the implementation of pretrial risk assessment tools. I looked to Boudin for an authoritative rebuttal. Having examined pretrial risk assessment tools as an investigative reporter, I knew they were flawed and had more potential to increase incarceration than to decarcerate. Boudin’s base supporters knew this as well. On the campaign trail, however, policy implementation is easy to sidestep, and Boudin had a powerful message about the immorality of monetary bail and the disadvantages poor people face when they come up against the criminal legal system.

“Of course,” Boudin replied to the chief of staff. He pivoted towards me and added, “Let’s give credit where credit’s due.”

In that moment, it likely made sense to appease the one ally he believed he had among the higher ranking officials in the office. Obvious backlash was swift, as was Boudin’s damage control. As I packed up the final box in my Los Angeles home in preparation for my family’s move to the Bay Area, my phone buzzed. Boudin fired me in a text message. When I finally was able to speak to him the following day, all I could think to say was, “You’re going to screw this up for all of us.”

A little over a year later, Boudin and I had both moved on. I had joined a grassroots organization battling mass incarceration and was drafting what would become my debut book, Reimagining the Revolution. Boudin was recalled. In the end, his attempts to address issues like cash bail and reduce the prison population resonated with voters in theory, but his inability to ensure public safety and his hedging on issues like police accountability left many Californians feeling vulnerable and betrayed by the very reforms they initially supported. In a significant way, Boudin’s ousting marked a pivotal moment in California’s relationship with progressive politics, catalyzing a widespread erosion of trust in the movement’s effectiveness. It became a symbol of progressive politics falling short of its promises, ultimately fueling skepticism about the feasibility and safety of reform-based governance.

In all, Boudin’s tenure revealed the dangers of equivocation and unsteady leadership within progressive politics—a reality that has cast a shadow over subsequent progressive initiatives in California. On Tuesday, Gasćon, who had left the Bay Area to run the country’s largest prosecutorial office in Los Angeles, was unseated by conservative Nathan Hochman. Voters approved Proposition 36, which reclassifies some misdemeanor theft and drug crimes as felonies and undoes much of the gains of Proposition 47.

Then there is the effort to remove involuntary servitude from the state constitution, a measure that has overwhelmingly passed elsewhere. Before Tuesday, seven states had amended their constitutions to remove the exception clause that permits involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime—-Colorado, Nebraska, Utah, Alabama, Tennessee, Oregon, and Vermont—-by an average margin of 70%. Nevada joined the list in this past General Election with 60% voter approval. Every time the initiative has been on the ballot it has succeeded with the exception of two consecutive defeats in California, once in 2022 and again this week.

The difference? Proponents of the measures in other states stuck to a single, unmitigated message: That slavery, and its identical twin involuntary servitude, do not define our values anymore and, therefore, have no place in states’ constitutions. It was a moral issue. In California, however, the message immediately focused on prison labor, a more obfuscated issue that provoked questions about punishment, labor shortages, and other issues most people in the state—not the abolitionist organizations that promoted the proposition, of course—struggle to reconcile. It became a logistical issue and the door was left open for voters to solidify harmful, outdated language en masse without shame or regret.

Californians did not vote against the principles underlying Prop 6 but rather against a measure whose messaging failed to connect with their sense of safety, justice, and clarity. When progressive leaders equivocate or present policies without a clear, straightforward vision, they risk alienating voters who may otherwise align with the core values of the movement. Either the movement firmly champions justice-based reforms, or it risks being diluted by compromising language that leaves voters feeling uncertain or unsafe.